Growing Our Own And More On The Bullseye Diet

It was mainly Peak Oil that drove me out into my garden with a new mission; no longer just to grow a few tomatoes for fun each summer, but in an effort to grow the majority of the food my family eats. I set out a goal of producing more calories than I consume on my own property and within 5 years. I called my project ‘Growing My Own’. But there were others factors tugging at me, entreating me to take personal responsibility for the needs of my diet.

It was mainly Peak Oil that drove me out into my garden with a new mission; no longer just to grow a few tomatoes for fun each summer, but in an effort to grow the majority of the food my family eats. I set out a goal of producing more calories than I consume on my own property and within 5 years. I called my project ‘Growing My Own’. But there were others factors tugging at me, entreating me to take personal responsibility for the needs of my diet.

And I can see now that there are lots of other people becoming interested in local food and they’re doing so for a variety of reasons. Some of them want to avoid the potential health threats increasingly associated with industrial agriculture. You can get your daily update of just what food has been recently recalled as a health hazard by visiting this handy website the U.S. FDA recall website. The fact that such a site exists is a telltale sign of our increasingly dysfunctional relationship with what we eat. To be sure there have always been local incidents of accidental food poisonings and the like, but now that our system of growing and distributing food is so centralized, the risk of mass contamination from food borne illness is much higher. My favorite example is the recent Castleberry’s Chili recall in which cans were literally bursting with botulism. In the face of all the human health problems swirling around the anonymous origins of industrial food, many people are now opting to get their food from known local sources.

Some people see local food as a social justice issue. It’s becoming more widely recognized that giant food corporations use money, or sometimes much more dubious means, to displace subsistence farmers in developing nations in order to gain access to cheap farmland; and later cheap labor as the displaced farmers now must work for money with which to buy imported food they once grew themselves. Or as my friend George recently put it, Now, if you’ll just sign over your third world natural resources and any infrastructure you have, we’ll send you paper which you can trade back to us for food…ain’t globalism grand? Add to that the subsidies embedded in the U.S. farm bill, recently renewed, that hands out millions of tax dollars to huge AgriBizCorps that then undersell struggling farmers in developing nations. It’s easy to see why buying local makes more sense in terms of global social issues, not least among them hunger in the third world.

But there is another more local reason to get your food from close to home; eating in such a way supports local communities. Why on Earth would I send my money half way across the country when I can put it in my neighbor’s pocket? Supporting local farmers through programs like Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) or just visiting your local farmers market helps share the burden and the benefits of farmers trying to grow food and sell it locally. This is a fast growing trend.

Some people have come to recognize another benefit of eating locally- it tastes better! What’s that you say? You’re store bought tomato tastes like cardboard? Of course it does. It was breed to be shipped long distances and sit on store shelves for weeks; and it has. If you want tasty varieties bred for eating and picked just yesterday and shipped only a few miles, you’ll have to visit more local sources. Maybe even your own backyard.

Other people are worried about the effects of global warming and the coming changes to the overall climate on Earth. Even a steady, gradual increase in global temperature would be difficult to deal with agriculturally speaking but we are likely instead to see a climate system thrown into disorder with wild swings in temperature during the course of individual seasons with some regions experiencing extreme drought while others flood, not to mention bigger storms. Add to this a rise in sea level that will increase the number of people displaced by climatic events and it could be a very tough time to grow food as our global climates changes out from under us. It is no wonder then that some people are seeking to secure their sources of food. And with security increasingly easier to archive as one approaches one’s own home, many people are looking to eat local or even grow their own food as a response to global warming. It’s also worth pointing out that those who look towards local food security as a response to climate change often do so with the knowledge that they are greatly reducing their impact on the warming of the planet by turning away from industrial agriculture. That system of growing food is by the way, responsible for a fair amount of the greenhouse gasses we put off into the atmosphere each year.

I dare say some people are even beginning to think about local food production as an issue of sovereignty. If as a community or a state or even as a nation, you can’t feed your people on your own, then you are beholden to others for one of the most important of human needs. I recently posited that a closer look at the collapse of the Soviet might be more appropriately focused on their need for grain rather than only on their declining oil and natural gas revenues which made it harder for them to buy grain. After all, you don’t have to buy it if you grow it yourself. Individuals and communities of all sizes are beginning to recognize this fact. It’s coming to be seen as an issue of state and national security. I think local food production should be part of local community planning for the very same reason.

So let’s review, we have a highly centralized food system that easily distributes food borne pathogens quickly to lots and lots of people, we increasing use the land base of people in the developing world to cheaply grow our food often at their expense, we line the pockets of far away companies at the expense of our local farmers, we settle for bland food bred to make the long haul across country, we pollute our planet and warm our atmosphere so as to have cheap cumquats when every we want them and we leave ourselves vulnerable to others in terms of meeting one of our most basic human needs, all by not eating local. I think it’s easy to see why people are beginning to reexamine the curious strategy of industrial agriculture.

For me though it was peak oil. My decision to become more self sufficient in terms of food production came from an examination of just how much industrial agriculture depends on oil and other fossil fuels. Global oil production is peaking, in other words there is more oil available at this point in history than there will be ever again. From this high point, worldwide oil production will decline no matter what we do. Likewise a peak in natural gas (NG) will occur within a decade or so. With a little research I discovered commercial pesticides are made from petroleum and commercial fertilizers are made from a feedstock of NG. Not a happy thought when you consider the coming decline in the availability of these nonrenewable resources. And it’s becoming more widely recognized that on average our food travels about 1500 miles from the farm fields to our dinner tables. When I considered the diesel fuel used to truck this food across the country I became even more worried about where my food would come from in the future; and what it will cost.

So my plan was to ‘Grow My Own’ and by doing so to remove myself and my family from a highly questionable system of industrial agriculture. I wanted to work to regain my own food sovereignty for lots of reasons. In other words I decided to garden like mad!

The problem is though that my goal of near self sufficiency in terms of producing all my own food was an extremely difficult if not impossible goal to achieve. Of course in parallel with my idea of growing all of my own food, a gathering movement of other people, fed up with industrial agriculture, was growing in size. This movement now includes all sorts of programs and strategies devoted towards other options for dinner. CSA’s, the 100 Miles Diet, the Slow Food movement, a resurgence in Farmers Markets, all of these practices have taken off and are proving more and more people with an alternative way to eat. I began to participate in some of them. I did this in concert with my efforts to grow more of my food, which has expanded into a cooperative effort to grow food with neighbors in multiple locations. In my neighborhood we are taking over a vacant lot and we are gardening in the sunny backyard of an elderly neighbor. And it has become increasingly clear that while I probably would never be able to grow all of my own food on my own property, there were overlapping system by which I could get healthy food grown nearby in ways that use fewer fossil fuels and produce less pollution.

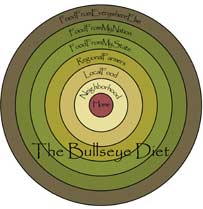

But being a philosophical sort of person, I needed a conceptual way to organize my increasingly entangled way of thinking about local food. These multiple strategies seemed interwoven and yet I wasn’t always sure where to focus my best efforts. And that is when the idea of The Bullseye Diet emerged. OK so at first I called it Concentric Circles of Eating. I know, how geometrically nerdy. But luckily my friend and co-author Sharon Astyk offered up a much more pleasant name and The Bullseye Diet was born.

The idea is to imagine sourcing your food as a good game of darts where the dart board represents your geographical region. A great shot ends up in the bullseye- your own home- eating food you have grown yourself. As you move outwards on the board, your next nearest food source is usually your best bet. How much food can you grow in your neighborhood? How about buying food from a farmer just outside of town? Can you get other foods from your surrounding region?How much can you obtain from within your own state? The idea is that the closer to home- the closer to the bullseye- the better.

Here is Sharon’s introduction to this new mental model of eating.

And here’s a link to audio of her talking to Jason Bradford of The Reality Report about The Bullseye Diet and about her upcoming book Depletion and Abundance: The New Home Front, Families and the Coming Ecological Crises

We both thinking existing ways of encouraging local eating, like the 100 Mile Diet, are great and work well within the bullseye strategy. This Bullseye model though places the consumer at the center where she or he recaptures the rightful role of producer. We have been told for so long in this country that we are first and foremost consumers and that notion has become pervasive in our culture. In fact the idea of a nation of consumers has replaced our national identity as citizens, as participants in our own lives and in our civil institutions. All our modern conveniences of entertainment and travel have offered the same concept and in doing so they have removed us as active and important participants in our local communities. We don’t talk with neighbors as we watch our children play each evening. We mainly stare at reality TV. We do not walk or bike where we are going, using our own muscles to get us there. We drive and burn a nonrenewable resource that pollutes our planet. But eating food from far away, this geographical disconnect from the very sustenance that keeps us alive, is at the heart of direct experience and we have given it up as well.

There are many reasons above to begin again to get involved in how and what we eat. Some of them are out of prudence, others out of loyalty and all of them I think out of common sense. But it is this idea of regaining our ability to feed ourselves by putting our own food on the table for our family, it is this idea that I think can jump start a revolution in rejection of excess consumption and the rampant materialism of our age. Moving from a nation of eaters towards a nation of growers will do more than shed our extra weight. It will directly address our reliance on others to do for us what we can do for ourselves and in doing so it will put us back in control of how we live our lives.It could be, dare I say it will be the first step towards a revolution.